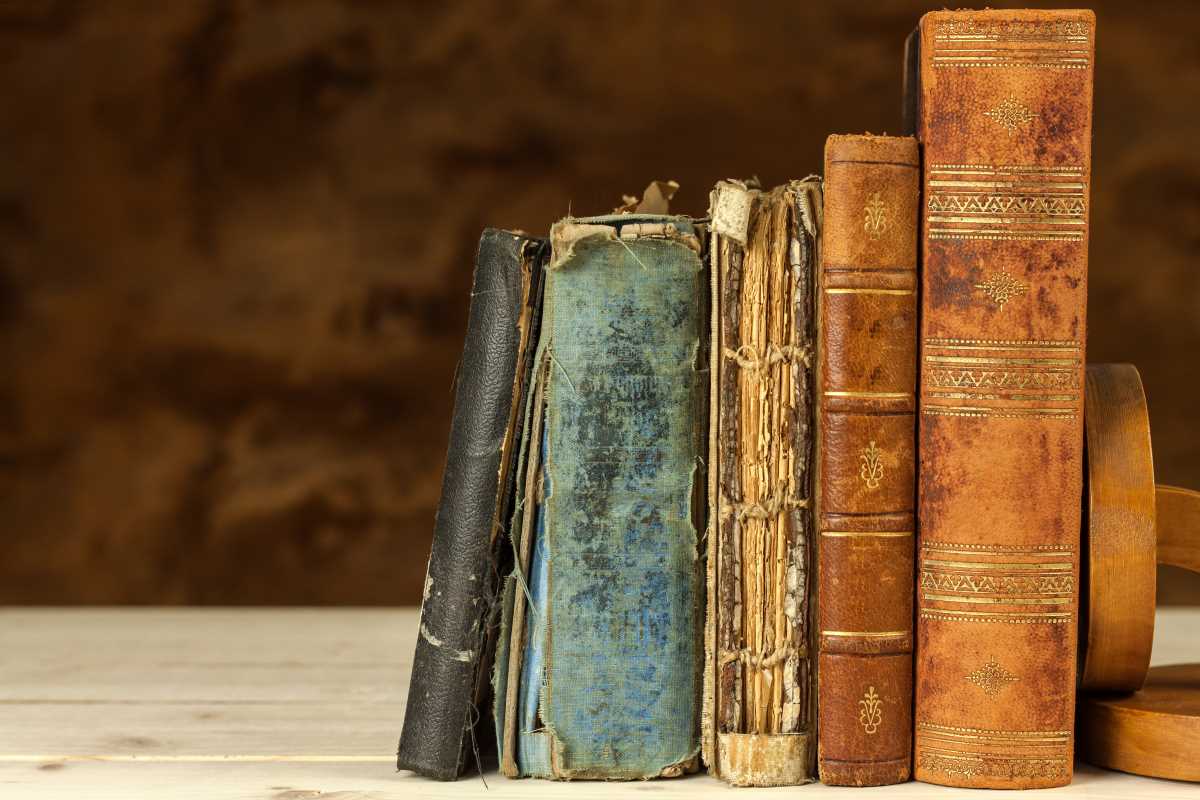

Fairy tales have always carried a sort of magic. We picture them as bedtime classics meant to inspire, comfort, or entertain. But if you take a closer look at some of their original versions, many are far from comforting. Beneath the enchanted castles and talking animals are stories rooted in hardship, pain, and gritty realities. Love meant sacrifice, magic often came at a price, and "happily-ever-after" didn’t always show up. These tales taught lessons, reflected fears, and captured the struggles of the societies that created them. Join us as we revisit some famous fairy tales in their original, darker form and explore why they remain captivating, even after centuries of retelling.

“Hansel and Gretel”: A Tale of Hunger

“Hansel and Gretel” is a chilling example of how folklore reflects desperation. Originally collected by the Brothers Grimm, the story is set against the backdrop of widespread famine in medieval Europe. During the Great Famine of the 14th century, crop failures led to mass starvation, and tragic stories surfaced of families abandoned to fend for themselves in the wilderness.

The iconic plot of “Hansel and Gretel” mirrors these grim times. With no food to sustain them, the parents in the tale make the unthinkable decision to leave their children in the forest. Then comes the gingerbread house, a symbol of bait and false hope, hiding the dangerous witch within. Her cannibalistic twist is likely a reflection of fears of how starvation could push people to their limits.

At its heart, the tale highlights themes of survival and resourcefulness. Modern versions highlight Hansel and Gretel’s cleverness in outsmarting the witch, but the story stems from a more sobering reality: when pushed to the brink, people were forced to make unimaginable choices.

“Little Red Riding Hood”: A Warning, Not a Rescue Story

You've likely heard "Little Red Riding Hood" told as a triumphant story of good conquering evil, with a brave huntsman swooping in to save the girl and her grandmother from the wolf’s clutches. But this cheery ending was a later addition to the tale. The original version captured by Charles Perrault had no such happy ending. Instead, it ended with Little Red Riding Hood being eaten by the wolf, a fate shared by her grandmother. There was no last-minute hero, no second chance.

Why so bleak? Early tellings served as grim warnings, particularly aimed at young women. The wolf symbolized predatory and deceitful men, and the story taught listeners to avoid wandering off the beaten path or being too trusting of strangers. Over time, more child-friendly versions emerged, softening the tale’s dark edges, though the underlying cautionary message about staying safe remains at its heart.

“The Little Mermaid”: Love and Loss

If you read Hans Christian Andersen’s original version of "The Little Mermaid," you’ll be hard-pressed to find Disney’s bubbly optimism. Instead, Andersen’s tale is haunting, filled with yearning, loss, and sacrifice. It tells the story of a mermaid who falls in love with a human prince and dreams of a life on land. But the conditions she faces to achieve it are harsh.

To gain human legs, the mermaid strikes a magical deal that will destroy her voice and give her excruciating pain with every step. Heartbreakingly, the prince doesn’t fall in love with her. He marries another, leaving the mermaid alone and her sacrifice unacknowledged. Ultimately, her sisters present her with a grim choice: to kill the prince and return to the sea. She cannot bring herself to do it. She instead dissolves into sea foam, illustrating the ultimate tragedy of unfulfilled love.

Andersen, a master at adding complexity and depth to his characters, used "The Little Mermaid" to explore themes of self-sacrifice, rejection, and the longing to belong. Far from the colorful adventures of the 1990 Disney film, the original tale is bittersweet, reminding us that love isn’t always enough to overcome life’s challenges.

“Sleeping Beauty”: A Disturbing Start

“Sleeping Beauty” has been passed down through generations, but early versions of the story are downright disturbing. One of the oldest written versions, "Sun, Moon, and Talia" by Giambattista Basile, takes a dark turn. Instead of being awakened by a kiss from a prince, the sleeping maiden Talia is violated by a king who discovers her lifeless form. She becomes pregnant and, disturbingly, only gives birth while still unconscious.

The dark tale doesn’t stop there. Talia only awakens when one of her newborn babies accidentally sucks the splinter of flax out of her finger, the same splinter that caused her irreversible sleep. What follows is a series of vengeful schemes and jealous feuds, including attempts by the king’s wife to cook and eat the children.

Later versions, especially the one by Charles Perrault and Disney's sanitized retelling, smoothed out these grim details. Yet, the original iterations of "Sleeping Beauty" speak to the unsettling themes of power and exploitation, where women’s autonomy was far from respected.

“Cinderella”: Justice is Served

The tale of Cinderella might bring to mind shimmering ball gowns and charming princes, but the earlier versions are surprisingly brutal. The Brothers Grimm version, for example, doesn’t shy away from graphic punishment for the wicked stepsisters.

To fit into the iconic glass slipper, the stepsisters slice off parts of their feet in a desperate attempt to fool the prince. However, their deception is revealed when their bleeding toes and heels give them away, thanks to the magical intervention of Cinderella’s pigeons. At the story’s conclusion, the same pigeons peck out the stepsisters’ eyes as punishment for their cruelty.

This version of "Cinderella" is worlds apart from the sugary Disney adaptation. It’s a tale of justice, yes, but the kind of justice that feels harsh and unrelenting. It carries a clear moral lesson that says deceit and cruelty will eventually be punished.

Why Were These Tales So Dark?

Fairy tales reflect the values and realities of the societies that created them. Life in medieval and early modern Europe was far from easy, with famine, disease, and violence being everyday concerns. Tales like these weren’t originally created for children. They provided moral lessons, coping mechanisms, and a way to make sense of a harsh and unpredictable world.

At the same time, these stories were communal, evolving as they passed from storyteller to storyteller. Cultural fears, norms, and lessons relevant to the people of the time shaped each iteration.

(Image via

(Image via